By Justin Hsieh, Staff Writer

Earlier this month, the College Board revealed a new score it will assign to students taking the SAT, which will aim to measure the level of adversity that students experience based on demographic data about their neighborhoods and schools.

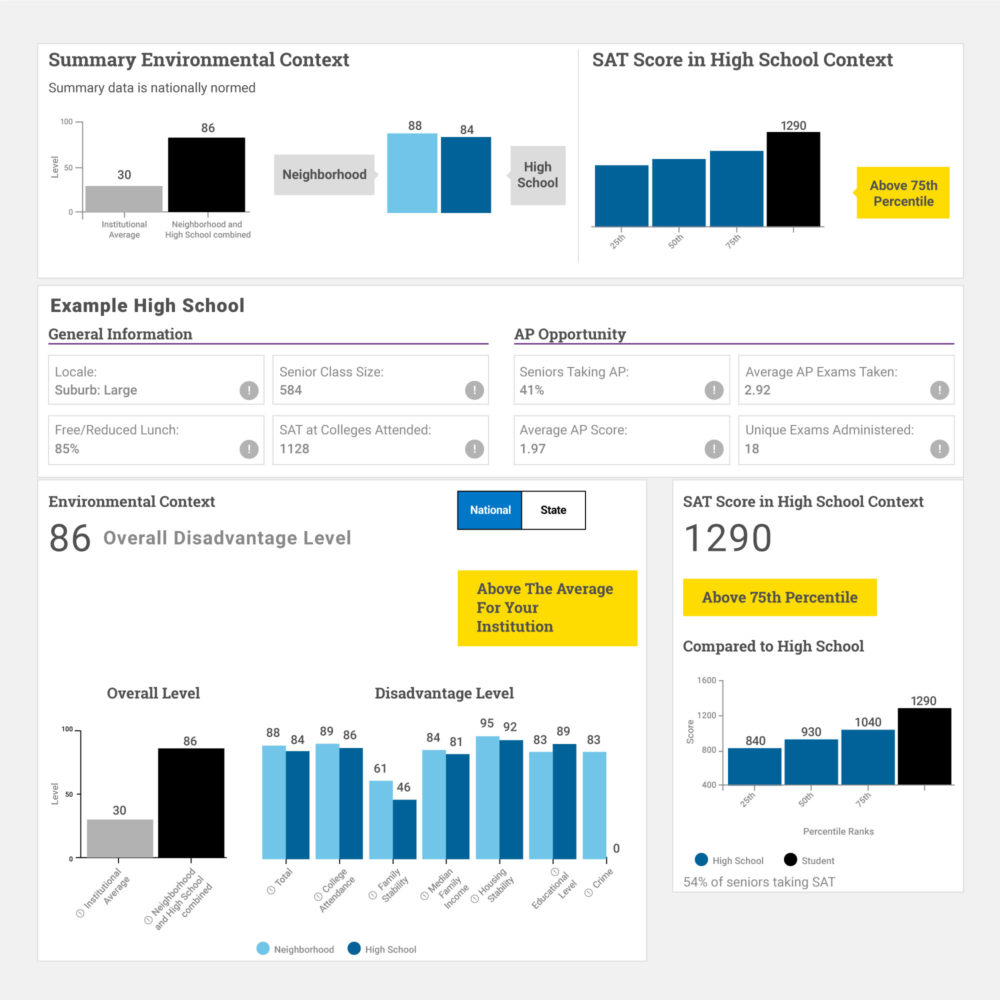

The score, officially named the “Overall Disadvantage Level” and called an “adversity score” by college admissions officers, is part of a larger collection of data known as the Environmental Context Dashboard (ECD) that the College Board will offer to colleges. The adversity score and other indexes in the ECD are calculated using a variety of data points about the schools that students attend and the census tract that they live in, including crime and poverty rates, median family incomes, and average SAT scores of other students at an applicant’s school.

“What the ECD doesn’t do is alter a student’s SAT score,” said College Board chief executive David Coleman. “A student’s score is his or her score. Period. The ECD simply provides vital context for that score. The SAT is a vital measure of achievement, but it doesn’t measure what you’ve overcome.”

The College Board began developing the ECD in 2015 as part of an effort to try to improve opportunities for students whose SAT scores may be affected by economic or social disadvantages. The organization conducted a beta test of the ECD with 50 schools in the most recent admissions cycle, and plans to extend the tool officially to 150 institutions this year and all colleges in 2020.

“[The ECD] is literally affecting every application we look at,” Yale University Dean of Undergraduate Admissions Jeremiah Quinlan told the Wall Street Journal. “It has been a part of the success story to help diversify our freshman class.”

Yale has been using a pilot version of the ECD for two years, and Quinlan says it has given admissions officers a more consistent and standardized way to evaluate students’ living and learning environments and contextualize their achievements. At Florida State University, another school involved in the testing of the ECD, Assistant Vice Principal for Academic Affairs John Barnhill said that ECD helped increase nonwhite enrollment from 37% to 42% in the school’s freshman class.

Since the Wall Street Journal first reported on the details of the ECD, the adversity score has been met with criticism on multiple fronts. Some argue that, rather than attempt to compensate for socioeconomic inequity in SAT scores, the College Board should address the problems directly by changing its test.

“If the score on your standardized test requires a separate algorithm to determine if the score is actually a valid measure of ability, then perhaps it’s time to fix the test itself rather than contextualize its scores,” said Randolf Arguelles, branch director of Elite Prep San Francisco.

Christoph Guttentag, Dean of Undergraduate Admissions at the highly competitive Duke University, disagrees, argued that some inequality is an inevitable and accepted part of standardized testing. Guttentag says he plans to use the ECD for admissions at Duke, which requires students to submit SAT and ACT scores.

“Everyone familiar with the college admissions process understands that it’s not a level playing field,” said Duke University Dean of Undergraduate Admissions Christoph Guttentag. “We’re always trying to understand each applicant’s context a little better, and I think this tool will be a positive step in that direction.”

Public Education Director Robert Schaeffer of the National Center for Fair & Open Testing is one of many who have used the introduction of the ECD to criticize the use of the SAT in college admissions altogether and advocate for the test-optional movement that is growing among institutes of higher education.

“Test-makers long claimed that their products were a ‘common yardstick’ for comparing applicants from a wide range of schools,” said Schaeffer. “This latest initiative concedes that the SAT is really a measure of ‘accumulated advantage’ which should not be used without an understanding of a student’s community and family background… In fact, schools do not need the SAT or ACT to make high-quality admissions decisions that promote equity and excellence.”

Others have questioned the methodology of the ECD, which uses data about students’ neighborhoods and does not reflect any specific individual circumstances a student may face.

“Assigning an adversity number suggests an influence that may not be operating for individual students, and it probably overlooks influences that are,” said former Missouri State University president Michael Nietzel.

At the same time, however, the ECD has been praised as an alternative to affirmative action as a campus diversity tool because it does not consider race or ethnicity for any of its metrics.

“This is what will give them a tool to achieve true diversity when and if they decide to stop using race, or if we’re ultimately successful in getting race out of admissions,” said Adam Mortara, a lawyer for the student group suing Harvard for alleged discrimination against Asian American applicants.

The ECD comes amid mounting recent challenges to the SAT and the college admissions system, including multiple affirmative action suits against prominent universities, security breaches in the SAT and ACT in the Middle East and Asia, a massive college admissions cheating scandal revealed earlier this year, and growing calls to completely eliminate standardized testing from college admissions.