By Karen Phan

You might not realize that these are some ways you’re destroying the environment by expanding your carbon footprint.

Landfills

Landfills are meant to keep solid waste and toxic materials out of the environment. Sounds good, but . . .

- Landfills emit a large amount of methane and carbon dioxide because of the decomposing organic material that makes up about two-thirds of the waste in the sites.

- Many of the items in landfills, such as electronic waste, also contain toxic materials.

- Leachate, or liquid that “leaches” from waste, contaminates soil and groundwater.

- Most types of wastes take a long time to break down, meaning landfills will only continue to grow and destroy the natural landscape.

The first thing you can do is reduce your solid waste production (including food waste) and compost. Stick to reusable items and buy fewer products with plastic packaging, which also calls for the industry sector to switch to sustainable production and packaging. Next time you’re at Starbucks, peek in their trash can and look at all of the single-use cups, then multiply that by every Starbucks across the world. If you bring your own reusable cup, you not only get a discount but remove yourself from the single-use game.

For more tips on reducing waste production, read this article from Conserve Energy Future, a website that promotes conservation and sustainability.

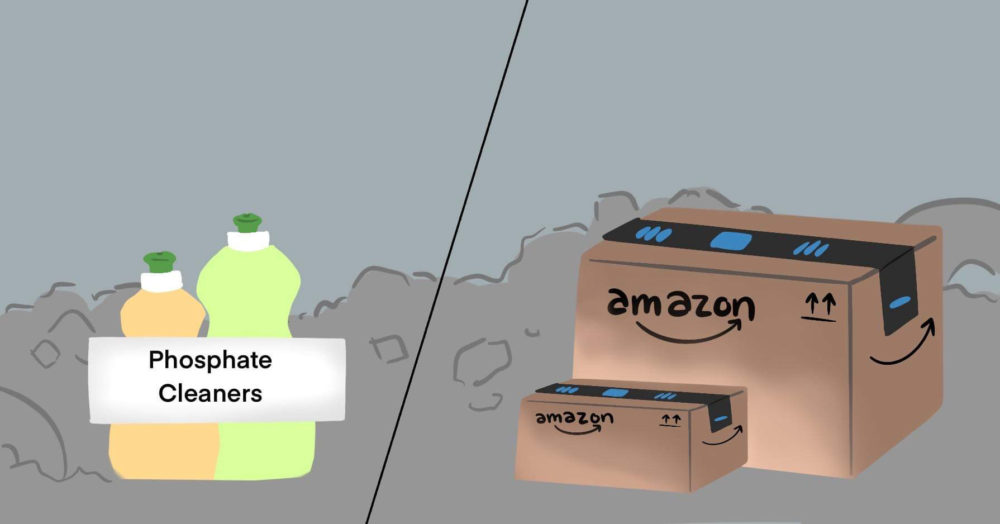

Online shopping

Online shopping is theoretically better for the environment because it emits fewer carbon gases than a person driving to a mall and back, but certain online shopping habits contribute to the growing carbon footprint of e-commerce.

- Fast shipping is less efficient and emits more carbon gases than standard shipping. Suppliers are forced to transport individual packages to meet next-day or two-day demand. With standard shipping, retailers maximize the space in boats, trucks or planes by bundling orders. The packages are then loaded onto full, rather than half-full or empty, delivery trucks.

- Returns via mail, especially from retailers overseas, “often feed into a global logistics system” to be processed rather than end up in a store or in-state warehouse, CBC Science and Technology Writer Emily Chung wrote in “Want it tomorrow? Some online shopping habits are terrible for the environment.” To avoid the carbon emissions that come with long-winded returns, check to see if you can return the item in-store.

- Items are often wrapped in plastic and bubble wrap/and or encased in styrofoam and packing peanuts in cardboard boxes or plastic mailers. If the materials are not recycled or disposed of properly, they may end up polluting the environment. Retailers also need to invest in sustainable packaging.

For more information on the carbon footprint of online shopping, read the MIT Center for Transportation and Logistics’ 2013 environmental analysis of US online shopping.

Phosphate Cleaning Products

You may already know that fertilizers pollute bodies of water and groundwater because of the nitrates and phosphorus in them. The same applies to cleaning products that include phosphate such as laundry detergent and dish soap.

Phosphorus pollution often leads to eutrophication, which is when the saturation of minerals and nutrients in a body of water cause algal blooms, depleted dissolved oxygen and aquatic life death. Some algal blooms contain toxic substances that contaminate food chains and webs through biomagnification.

The United States banned phosphate laundry detergents in the 1990s and some U.S. states have banned phosphate dish soap, but phosphate remains a common ingredient in all-purpose and industrial cleaners because of its effectiveness in cleaning.

Although phosphate cleaning agents still exist, those that don’t contain them also exist. There are phosphate-free store-bought cleaners, but you can also make your own homemade phosphate-free cleaner. Here are a few guides to identifying phosphate products:

Environmental Working Group’s Guide to Healthy Cleaning

The Environmental Working Group’s Skin Deep Cosmetic Database

For a simple breakdown of phosphates and phosphorus pollution, read this article from The Spruce, a home-and-garden website, and “Phosphates in the Environment” from Water Research Center.