By Jennifer Trend, Staff Writer

Novels are a large part of FVHS’s English classes, yet in World Language classes, books play a very small part of the curriculum, and the classes focus on more short stories or texts. So why are there no novels?

The main justification is because of the time and resources it would require to implement books, whether that be children’s or novel length books.

“One [problem] would be that with the curriculum that we have currently, the district wide adopted curriculum, would be very challenging for us to fit in time wise reading a book with our classes and cover all the other curriculum that we have to teach. Another [problem] is resources obviously. There would be an expense to purchasing books and our district has provided us with textbooks [and] we don’t necessarily have funds to buy separate books as well,” said World Language Department Head Jim Diecidue.

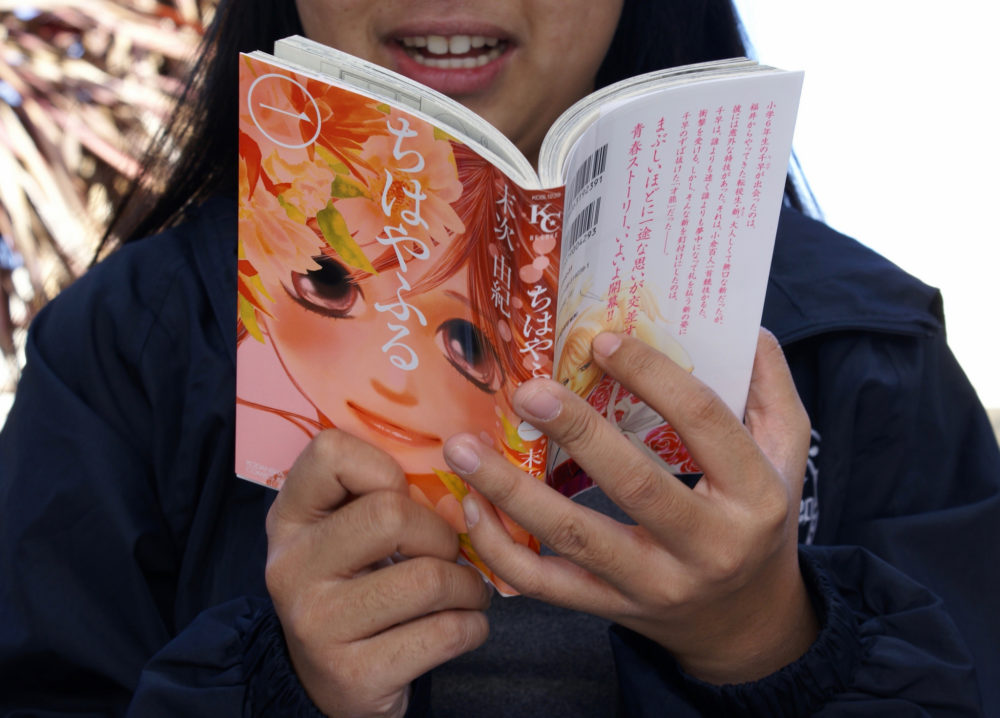

“I don’t think students are at that level to read full length novels,” said Japanese teacher Saori Tanaka.

The only full length book being read is “The Little Prince” by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry in French Four/AP, a book about a prince who travels to different planets and meets different person representing troubles in society.

But reading is a big part of the language classes even if it is not at the scale of a full length novel. Teachers introduce a variety of readings ranging from one to three pages such as newspaper articles, menus, short stories created by the teachers and excerpts from books that tie into the lesson or theme. Students often read fables or short stories.

“[What] we use in the lower levels are things that we come up with or found that can allow students that accessibility of understanding what they read while still being challenged to interpret it and make sense of it,” said Diecidue.

“I think [fables] teach cultural values and they also shares a part of the culture,” said French teacher Ashley Houlette. “It’s a cultural product that other people in the French speaking world recognize and know and reference in their lives. And so it helps students potentially connect with other people in that culture who are aware of these same stories and share these same experiences.”

With these texts, teachers create assignments ranging from translation to reading-check questions to drawing the text to creating their own alternative ending depending on the level and how in depth the teacher wishes to go.

“At the end of [“The Little Prince”], I ask students to identify with the book and to compare it to other stories they know and to create something,” said Houlette. “And that usually takes different forms- some years I’ve given students the option of writing an extra chapter… in order to make the story more personal, and I think it helps students take ownership of the language and of the story and practice what they’re reading.”

In Japanese Four/AP, students read a variety of mukashi banashi, a term for Japanese fables or folktales, create videos based on the folktales.

Reading texts can help you learn and improve in a language because you’re seeing the vocabulary or grammar structures in context and not as a solidarity thing in a textbook. Just like reading for English can help you learn and improve in English, the same is for foreign languages.

“I think [reading] does [help a student]. I think that when you read you have this imagination and so you become more creative,” said Tanaka.

“[Introducing books] would take a good amount of time for us to really work with and that would mean that we would have to restructure our curriculum that would be a big task at hand,” said Diecidue. “Not to say that it couldn’t happen but it would be a challenge to make that big of a shift. There are some places that have done that and have shifted to more of a book based curriculum. We’re not there right now at this point.”