By Hien Bui

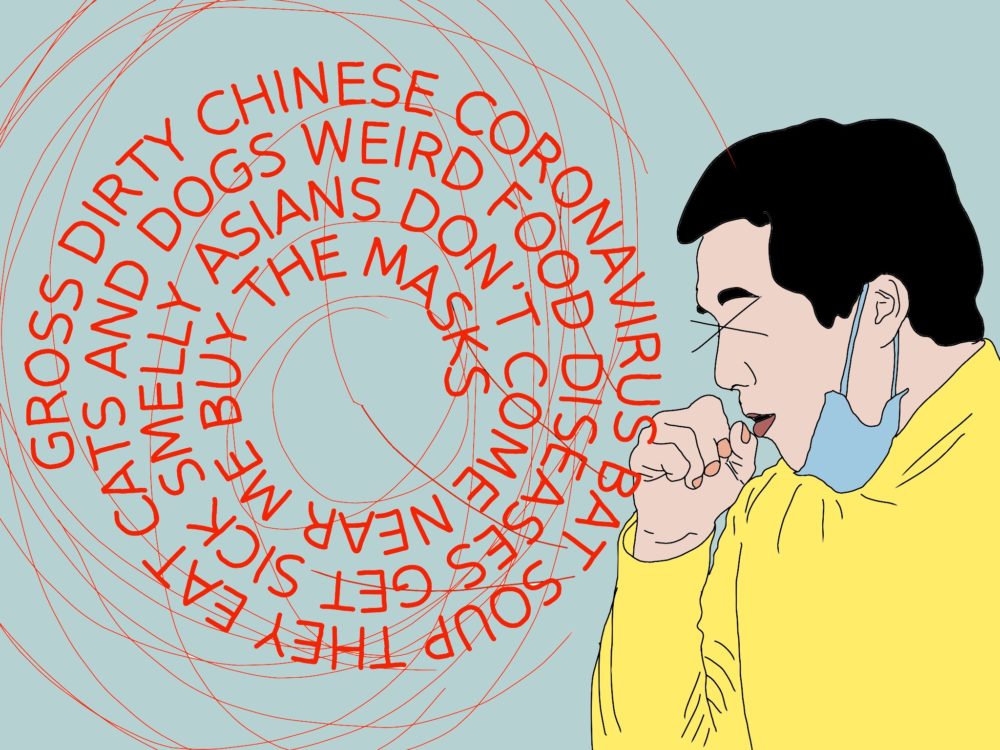

The 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) is in your conversations as you go about your day thousands of miles away from the outbreak’s epicenter; your news cycle as new information trickles in with every passing second; your social media as you watch an “informational video” that blames a Chinese person eating bat soup for the possible pandemic—it’s inescapable.

As the world becomes infected by fear alongside and far beyond COVID-19’s reaches, the heightened prejudice towards Chinese and Asians joins a historical pattern of xenophobia that we need to address.

The breakouts of other strains of the coronavirus family, such as the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome, led to stigmatization and discrimination of Asians. “SARS-phobia” was fear and suspicion of any person who looked Asian with no thought of their real nationalities or chances of having the illness. People became less likely to come forward with symptoms as they feared to further be ostracized when diagnosed.

Xenophobia was also a driving force behind the Ebola and HIV/AIDS narratives as the groups that the diseases were most affiliated with were blamed and alienation. New extremes crossed with the latter, such as when HIV/AIDS was criminalized and those who were HIV-positive were forced to disclose their medical information under the duress of law.

But unlike the times when SARS and HIV/AIDS caused panic, fear, a contagion in its own word, runs more unchecked than ever because our world is now extremely globalized. When anything and everything is out on the world stage and the Internet in a matter of seconds, it’s harder to contain panic in the community.

This fear turns hateful as paranoia and self-preservation provide an outlet for pre-existing or internalized prejudices. Since reports of coronavirus first broke in late 2019, Asian communities have been scrutinized under this new wave of caution turned discrimination.

The rise in stigmatization has come in many forms, ranging from social media comments under Asian content to the downright refusal to give an Asian man CPR out of fear of catching the virus. The University of California, Berkeley reasoned that xenophobia was a common reaction to coronavirus amidst news nationwide of racially-fueled attacks with a clear, defining anti-Asian sentiment.

Xenophobic tirades are filmed and posted as the virus gives prejudiced people an elevated soapbox to disparage others. In San Francisco, an incident between an elderly Asian man collecting cans and a neighborhood group turned aggressive and went viral.

Asian businesses hurt financially as people decide they can’t take the risk to enter any shops. French newspapers with “Yellow Peril” and other derogatory headlines splashed across their front pages lead to citizens creating the hashtag #JeNeSuisPasUnVirus, meaning “I am not a virus.”

Racist and xenophobic mentalities are virulent and aggressive, affecting anyone who has even the slightest relation or similarity to Chinese people. Such a person also becomes the other, the them in “us versus them” and the enemy. Their humanity doesn’t matter, the illness they might carry does.

Xenophobia scapegoats entire communities, detracts from the solidarity the world needs in the face of these crises and generalizes an entire group of people under blanket statements rooted in ignorance than actual merit. Playing the blame game is easier than trying to understand, but it doesn’t solve any part of the epidemic.

No amount of bringing down the Chinese, hate speech and violence will accelerate a cure. What is helping the cure effort is countries actively sharing information and technological advancements that continue to happen.

As our reactions to these threats to public health improve over time, what the general public can do is not feed into fear-mongering and misinformation and, instead, have compassion for one another and those afflicted.