By Kevin Doan

After reading the newspaper or coming fresh off of social media, it is common (sometimes even expected) to see humanity as opposed to itself. People tend to paint the world as being embroiled in a constant inferno both metaphorically, in matters of racism and disease, as well as literally, in matters of climate change and the burning West Coast of the United States.

Yet Steven Pinker, Johnstone Family Professor of Psychology at Harvard University, is still able to see through the smoke and articulate a compelling case for the contrary.

The world, as presented by Pinker, isn’t a utopia or even remotely close to one. Rather, its imperfections present a continued opportunity to get better – an opportunity to which the world has the ability to rise.

In his book “Enlightenment Now,” Pinker builds atop the optimism he’s established throughout his career, using comedically framed claims with a solid grounding in data to right your perspective of what humanity can do.

For the population of most nations throughout history, the common cause of death they have faced has been disease. Now more than ever before, that fact too has entered the limelight of global attention, but—even if the medical innovation feels minuscule in comparison to pandemics of the current and past—the facts continue to present an opposing narrative.

Pinker takes the example of drinkable water, a commodity only obtainable for mass consumption within the last century. In African countries currently deprived of potable water, countries in which drinking water and waste disposal are often from the same source, diarrhea (caused by the aforementioned practices) is the third leading cause of disease and death for children under 5 years old. It wasn’t until the advent of chlorination, a decontaminating process, that our stores of water became expendable for sanitary and consumptive purposes.

This technology, as predicted by Pinker, has saved an estimated 177 million lives. Pinker also points to a recent decline in inequality, presenting a global inequality index (calculated by metric of international dollars of disposable income per capita) that has dropped significantly between around 1975 to 2000. Selecting a more relatable dataset for his audience, Pinker displays an inequality index (calculated by disposable income per capita) for the United States and the United Kingdom, both of which saw sharp declines beginning in about 1930. All inequality decline is a consequence of our world shifting towards a market economy with countries being able to spend more today on their poorest than before the 20th century (when they spent nil).

The compelling aspect of Pinker’s book has nothing to do with politics but comes chiefly from logical contemplation as well as uncompromising statistics, some of which have been augmented by the media to push an adverse agenda. The facts exist; our world is not perfect, but if trends tell us anything, we are getting better.

Having examined the statistics and done research of my own, I too believe that the world is getting better. Even if our current entanglement in a global pandemic makes the world seem bleak, analyzing our reaction to similar crises in the past and looking at encouraging trends in poverty, life expectancy and other fields will reveal that the human condition is indeed improving.

It is no secret that the media skews towards covering the extremes of our society; our inherent vigilance is programmed to prioritize bad news as a method for survival. For that reason, we’d rather watch news coverage of the next plane crash or protest our government’s complicity in the disintegration of glacier shelves than flick through the minutiae of car safety and educate our social circles on the importance of financial education. Anything without grand results (or consequences) remains outside the realm of our attention. Thus we must take initiative to consciously seek out and compare our intuitive perceptions to come to a rational conclusion. My message is not to misconstrue information to fit a utopian image but rather to deny our natural notions when they do not fit with reality.

In recent times, a significant portion of our pessimism has been directed towards disease and our reaction to it, which may seem logical in the midst of a pandemic. However, contrasting our current situation with like incidents of the past reveals a clearer picture of our current performance.

Comparing the deaths (of all causes) at the peak of the 1918 H1N1 pandemic (Figure A) with the current COVID-19 pandemic (Figure B) in the subset of New York City, there exists a clear archetype between the two statistics with both remaining stagnant before the advent of either diseases then spiking as those diseases spread. Looking at change alone, the effect of H1N1 on New York City is higher than that of COVID-19. There exists a ~50 million median death discrepancy between the two eras.

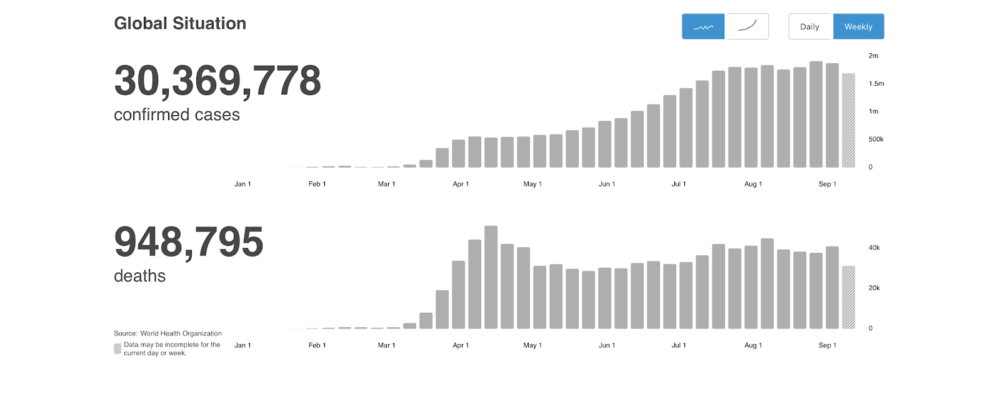

Comparing COVID-19 statistics alone, from the beginning of this year to now there is a clear stagnation in confirmed cases (Figure C) and death (Figure D) growth, the result of our greater knowledge of all aspects of the disease.

Diverting our scope away from disease and to a larger image of our intelligence, if the belief of the IQ is of any credibility then that marker is a clear indication of our growth.

In a study of the Flynn Effect (Figure E), researchers Jakob Pietschnig and Martin Voracek found that within a participant pool of 4,000,000 people over the span of 105 years, there has been consistent and significant growth in IQ. Attributing factors include growth in fields of education, nutrition and technology.

If any conclusions should be made about our world it should be concerning its ability to grow. The world has become accustomed to pessimism; the assumption of its eventual demise and our defeatist mindset paints our perception of humanity red.

The facts, however, show that perspective to be false. We should wake up in the morning knowing that the world is a better place not because some of us may be trying to change our innate negativity but rather because the facts demand so. The evidence is there, the case has been made: humanity is getting better.