By Camelia Heins

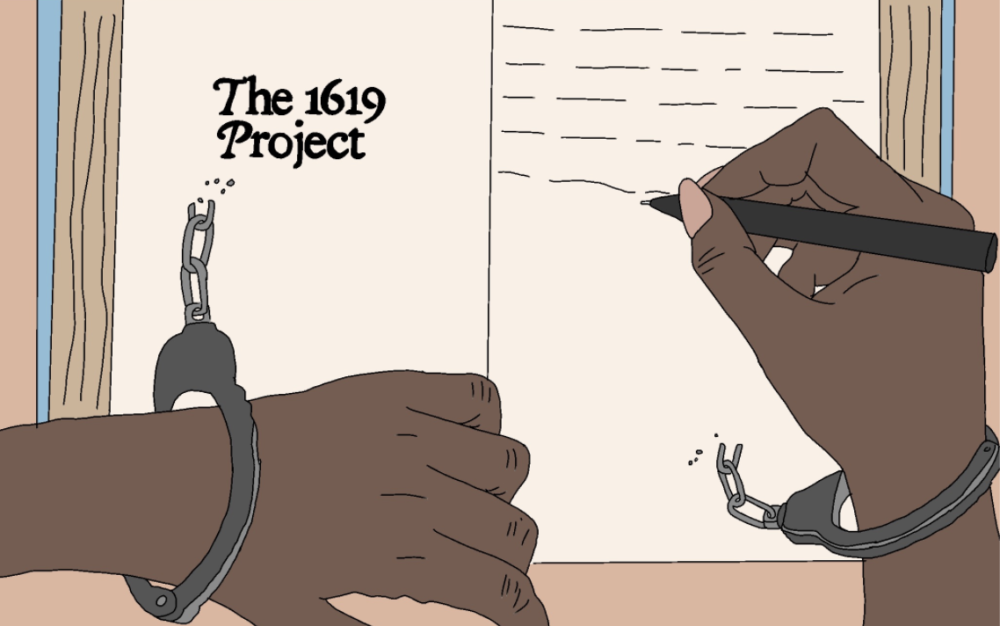

In the midst of Black Lives Matter movements and racial tension across the nation, the first step should be to educate the public on the systemic racism present in our nation’s history. But all bets are off as President Donald Trump blatantly rejects “The 1619 Project,” an ongoing project by the New York Times that focuses on the year 1619 when enslaved people were first brought to this country.

We need change, and we have to start at the roots—that means education. Whether it be “The 1619 Project” or merely an increase in diverse works, educating upcoming generations of the wrongdoings concerning slavery and injustices against Black Americans is necessary for ultimate racial justice in the future. Education is the key to learning from the past and rewriting the future.

Trump’s threat to pull funding from California schools that implement the Pulitzer Prize-winning series into the state’s curriculum isn’t only insulting to the Black visionaries involved but is also a step in the wrong direction. Haven’t the months of Black Lives Matter movement protests, marking the world’s largest civil rights movement, and trending #JusticeForBreonnaTaylor hashtags said enough?

Recent polls show that Americans of many backgrounds want change in terms of racial justice and support an anti-racist education that Trump rejects.

According to a Southern Poverty Law Center poll, an overwhelming 70% of adults surveyed nationwide support an anti-racist education. More specifically, 67% supported a deeper education in the “history of racial prejudice and violence, including slavery.”

Trump claims that California is implementing “The 1619 Project” into their curriculum to distract from the fact that his administration doesn’t have a comprehensive plan on creating a more diverse and inclusive education. Considering his administration removed Obama-era grant programs to increase diversity in public schools, opposed Affirmative Action and ended diversity training in federal agencies, diversity is the least of Trump’s concerns.

Instead, Trump established the 1776 Commission and called for “patriotic education.” Few details have yet to come out about his so-called “patriotic education,” but a White House’s statement says the curriculum plans to “encourage our educators to teach our children about the miracle of American history.”

If Trump’s plan is to teach about the “miracle of American history” and promote patriotism within our country, why didn’t he do it earlier? If he really cared about patriotism, why is he announcing this plan now, in response to his rejection of “The 1619 Project”?

It simply isn’t the right timing to be vaguely preaching about patriotism after months of nationwide racial protests. The truth is that this isn’t an act of patriotism, but rather a political move to suit his agenda.

Some, including Trump, argue that using “The 1619 Project” is an example of indoctrination, the process of teaching certain beliefs without questioning them. Indoctrination is typical in authoritarian regimes such as Russia’s military-patriotic education of children in Crimea. However, implementing “The 1619 Project” into school curriculum is far from the idea of indoctrination.

The Atlantic staff writer Clint Smith said it best in his opinion article: “[T]he truth is that our country is not made worse by young people reckoning fully with the legacy of slavery.”

Learning about the consequences of slavery and all factors that impacted the legacy of slavery shouldn’t be this complicated.

Young people being given more sources from multiple different angles isn’t indoctrination, as Trump calls it, but instead simply an expansion of education. Increasing the sources used when discussing a multi-faceted topic like slavery allows young people to make changes and responsible decisions when presented with modern-day issues on race. Restricting certain sources in the case of slavery, especially those written in the perspective of Black Americans, is damaging and one-sided for our education system.

Much of our American education system could already be seen as one-sided. Currently, the Texas Board of Education controls much of the textbook industry—and has been controlling their side of the narrative for years. Textbooks approved by the Texas Board of Education lack specific information concerning Black, LGBT and Native American histories.

After “The 1619 Project” was published, controversy and misconceptions about the project spread quickly. A group of historians sent a letter to the editors of the New York Times with their criticisms of the project. Although the letter “applaud[s] all efforts to address the enduring centrality of slavery and racism to our history,” it criticizes certain misleading facts and interpretations from “The 1619 Project.”

The New York Times editors responded and denied the presence of any unfactual information, claiming that, “Historical understanding is not fixed; is constantly being adjusted by new scholarship and new voices.”

The writers and editors of this project thoroughly researched information, consulted historians and scholars and openly accepted constructive criticism. “The 1619 Project” doesn’t intend to mislead or lie to the public, but rather introduce a new interpretation and perspective of the year 1619 and the history of Black Americans.

Further misconceptions about this project have been directly shown through Trump’s criticisms, even going as far to call an education framed around race as “a form of child abuse.” The real disservice to American students is a lack of information needed to create responsible decisions in the future. The students of today should learn about all perspectives, from multiple different sources, to become the citizens of tomorrow.

A diverse education that spans across multiple topics helps students recognize different cultures and perspectives within their communities, feel empowered to make a change and feel represented in their education system. We as students have the ability to create changes for our future—and it starts with our education.