By Jenny Tran

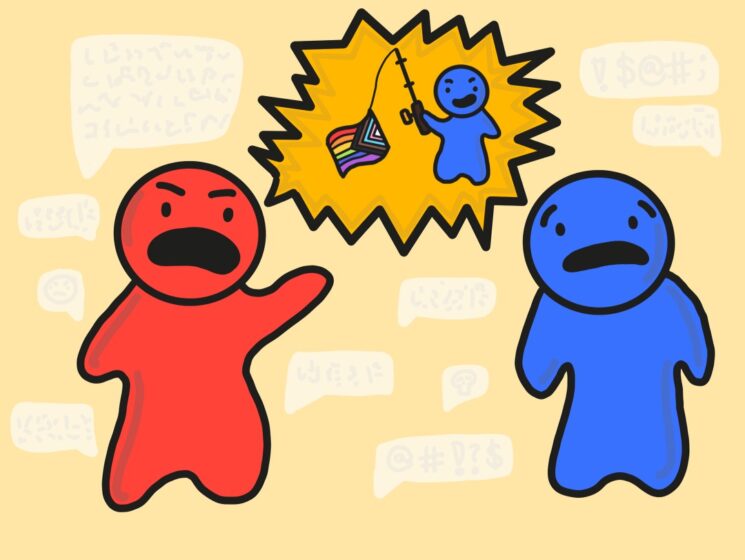

Over the past decade, the word “queerbaiting” has been thrown around online spaces—a term used to describe a deceptive marketing tactic that feeds on queer audiences.

Precisely, companies suggest or hint at the idea of LGBTQ+ content in their media, only to end up not delivering it. It can be frustrating for viewers who want to see such representation in the shows and movies they watch, their hopes of two same-sex characters getting together ultimately falling flat in the end. Complaints of queerbaiting have been made to all sorts of popular media, including shows like Sherlock and Supernatural, where fans have felt that they were getting led on and “baited” by false promises of queer characters.

Stepping outside of fictional spaces, however, there is a popular belief that this idea—of pretending to be queer for the sake of profiting off audiences—can also be applied to real people.

From Harry Styles to Billie Eilish, celebrities are no exception to the onslaught of queerbaiting allegations. When celebrities engage in queer behavior without explicitly labeling themselves as queer, they can easily become the target of such accusations, with people believing that they are simply pretending in order to gain favorable views from their audiences.

However, accusing real people of queerbaiting is extremely invalidating, and it actually does more harm than good.

Whereas in fiction, where the origins of queerbaiting accusations are often black-and-white (e.g., two characters of the same sex are hinted to be more than friends, but that’s really all they are), it is much more complicated when it comes to real people.

We’re so used to the idea of deeply analyzing fictional characters that we often, maybe unintentionally, project this scrutiny onto celebrities. But, when it gets to the point where they aren’t seen as humans but rather characters that we consume, that is where it becomes dangerous.

When we accuse celebrities of queerbaiting, we aren’t attacking companies that create fictional media for our consumption anymore, but rather the real people themselves. And that’s the thing—real people aren’t fictional characters. Queerbaiting should only be limited to fictional media, and when these accusations are applied to public figures, it is implied that they owe it to us to be completely transparent about their sexuality.

In truth, sexuality often isn’t an easy matter to approach. It isn’t the same for everyone, and people need time to figure themselves out and what they like. Some people simply don’t feel the need to disclose their sexualities to the public or even give themselves a label.

Queerbaiting accusations, however, completely undermine this idea. They assume that everyone has themselves figured out and whether they are queer or not. They give off the impression that people are only allowed to act a particular way if they are completely certain that they are attracted to that specific gender, which essentially claims that all inherently affectionate behavior has to have some romantic connotation to it.

Especially for people who are still figuring themselves out, this puts unneeded pressure on them to give themselves a label. In reality, though, we are not entitled to know such information about celebrities, and they shouldn’t feel the need to disclose that about themselves if they don’t want to.

Ironically, calling someone a queerbaiter essentially gives them a label already—one that assumes that person is not queer, or straight. It falls back on the heteronormative approach that unless a person outs themselves, they are straight by default.

There are some instances where queerbaiting accusations led to extreme consequences on the person they were fired toward. Take Kit Connor, for example, who stars in the popular queer Netflix show Heartstopper. In the show, Connor’s character, Nick, tackles with his sexuality throughout the first season but ends up feeling comfortable with who he is in the end.

Unlike his character, however, Connor hadn’t explicitly stated his own sexuality to the public. And, when he was seen holding hands with his female co-star, he was under fire for queerbaiting and being accused of projecting himself in a queer way despite being straight.

The allegations got so bad to the point where Connor felt the need to out himself on Twitter in order to cease them, despite having stated before how he didn’t feel the need to label himself publicly. He also mentioned how uncomfortable he felt about speculations around his sexuality even though he himself was comfortable with what he knew about himself.

While there are times when straight people publicly present themselves in ways that make them appear queer, accusing them of “pretending to be queer” doesn’t make sense when they’ve already said that they’re straight. It’s best to just take their word for it unless they state otherwise.

Regardless, whether a person decides to publicly come out or not, no one should feel pressured to publicly disclose their sexuality if they don’t want to. Queerbaiting allegations should be kept within the fictional realm and not be targeted toward real people.

While it’s frustrating to not see the representation you want to see, you have to remember that people don’t exist for the sake of representation. It is their choice whether or not they want to reveal that part of themselves to everyone, not ours.